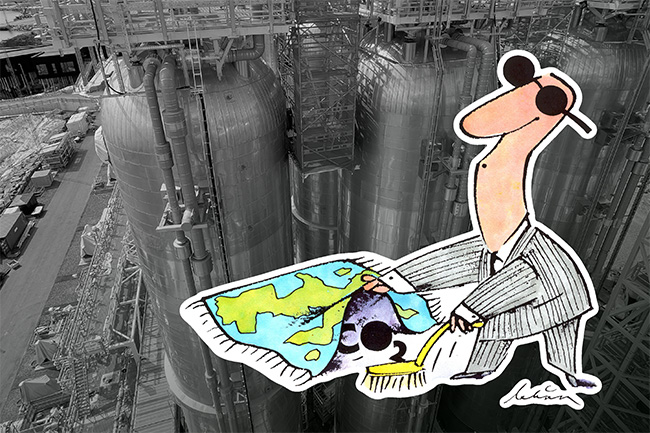

There is a notion that there is a large group of emissions that are hard to abate, and therefore need either CCS on those emissions (effectively ‘turning the chimneys down’ into the underground) or negative emissions (to suck back CO2 from the atmosphere after it has been emitted). This notion has gone viral in the climate policy discussion. It is now the main justification for CCS.

The catch phrase “hard to abate” is now repeated by a large number of industrial lobbyists as well as official bodies. A few examples:

“Industrial carbon management solutions will be most needed in ‘hard-to-abate’ sectors where mitigation options are limited. So far, according to the submitted draft National Energy and Climate Plans, the main applications for capturing CO2 identified by Member States are in industrial processes including cement, steel and natural gas processing sectors, as well as in the production of electricity (especially from biomass) and of low-carbon hydrogen, refining processes, waste incineration and thermal heat production.”

European Commission, 6 February 2024

“Hard-to-abate” as a concept is clearly the result of a massive lobbying effort. Otherwise you would hardly expect this heterogenous group of corporate interests and bureaucrats to be repeating the same message. It is easy to find many similar statements.

But “hard to abate” is a problematic concept.

First, the very existence of a large group of large emissions for which we have no mitigation options should be called into question. Even assuming that there are some emissions that are indeed difficult to abate, is it really such a big problem that it requires a very big solution? If it is not very big, why not put all the effort into reducing emissions by using less fossil fuel?

Second, how much of a solution is CCS? How large a share of all present emissions at a plant can it avoid, rather than just those from a point source within the plant? It is never 100 percent, and may be closer to 50 percent. And how big is the “parasitic” energy loss or energy penalty due to capturing, compressing and storing the CO2. CCS “increases the fuel requirement for electricity generation by 13–44% according to the IPCC,[1] but is it 13 or 44%?)

Third, how fast can CCS be deployed, compared to other options? When will it start to abate on a relevant scale?

Fourth, the supposed solution – “negative emissions” – tends to focus on technological measures, not on nature-based solution such as afforestation and restoration of wetlands. The IEA does so,[2] the EU does so, at least the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change in its assessment of various options for carbon removals (in other words negative emissions).[3]

The technological measures are Direct Air Capture (DAC), or using huge vacuum cleaners to suck CO2 out of the air, and Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage. Are DAC and BECCS really credible, technically and economically? How effective are they: how much CO2 can they capture, at what cost?

If negative emissions are needed, what evidence is there that DAC and BECCS are cheaper, faster, safer and surer than wetland restoration, afforestation and somewhat reduced logging. The data is not there, and for example the two sources referenced above tend to say that DAC is very expensive, BECCS is relatively expensive, while at least some of the nature-based solutions are cheap. The role of BECCS (as described by many Integrated Assessment Models for the IPCC) would also be limited by land use “typically, one to two times the area of India”[4] according to two eminent climate scientists.

Fifth, CCS cannot be a permanent solution in the sense that we will bury billions of tonnes of CO2 every year, forever. As Gasunie, the Dutch gas infrastructure company has put it: “Carbon capture is a temporary solution in the energy transition”.[5] Sooner or later, we will have to find other production methods, or adjust consumption patterns to stop emitting more CO2 than Nature can handle. CCS is, intrinsically, a transitory measure. Something will have to come after it. So the question is why we should we not go directly for that solution to each of the supposedly hard-to-abate emissions.

For society at large, it makes little sense to invest first in one extremely expensive system and then to switch to another extremely expensive system.

In the oil and gas system this would mean continued investment in oil and gas wells, CCS at gas processing plants, CCS at power plants, millions of new gas boilers, thousands and thousands of kilometres of CO2 pipelines, CO2 ships and CO2 storage facilities. Because such a system cannot capture anywhere near 100% of the CO2, it would have to be complemented with negative emission technologies such as BECCS and DAC.

After the completion of such a system, a new one would have to follow: the gas boilers will be replaced with heat pumps, the fossil power plants will be replaced with wind and solar and batteries, or other forms of storage, with many more power lines, factories to build wind and solar power etc, while the CCS structure is dismantled.

It is effectively one system for the price of two. The justification might have been that we need CCS temporarily while we wait for wind and solar to ramp up and get cheaper. But although this may once have sounded reasonable, it is not so now.

What makes little sense for society at large, does make a lot of sense for the oil and gas industry and for the governments that depend on revenues from them. Oil and gas is a very big business that can make a great deal of money by carrying on business as usual for an extra year or an extra decade.

Even the very pro-CCS International Energy Agency has warned against too much reliance on CCS:

“The industry needs to commit to genuinely helping the world meet its energy needs and climate goals – which means letting go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution”[6] said its executive director, Fatih Birol, in 2023 before COP 28, and was immediately attacked by the oil cartel and lobby OPEC for “vilifying” the oil industry.[7]

The concept of hard-to-abate was probably developed for lobbying purposes, certainly not for scientific use. The “sectors” are not well defined or logically structured. Some of them are not hard to abate. Even the concept of abatement is unclear; the “sectors” usually refer to fossil CO2 emissions, but some of them refer to biogenic CO2 emissions, which creates a risk of double counting. Either biogenic CO2 is considered as climate-neutral, in which case BECCS is meaningless. Or it is considered the same as fossil CO2. There are arguments for both sides, but a blurred distinction is much like moving the goalposts.

For more detailed arguments about CCS, see for example:

https://www.ciel.org/issue/carbon-capture-and-storage/ https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/challenges/fossil-fuels/carbon-capture-and-storage/

“The world needs a fair, fast, full, and funded fossil fuel phase-out”, says the Climate Action Network.[8] CAN represents more than 1900 civil society organisations, and theirs is the standpoint of the whole environmental movement, including AirClim.

This view is not necessarily shared by the producers of fossil energy, the big users of fossil energy and their lobby organisations.

More details can be found in the following AirClim policy briefing.

Critical analysis about different industry sectors like steel or cement and the need for CCS solutions are presented in this section.

[1] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_Chapter_06.pdf p 6-38

[2] https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/181b48b4-323f-454d-96fb-0bb1889d96a9/CCUS_in_clean_energy_transitions.pdf see table 2.3, page 80, which does not even mention wetland and mangrove restoauration but expects direct air capture to have a potential of up to 1000 billion tonnes.

[3] https://climate-advisory-board.europa.eu/news/new-report-from-the-eus-climate-advisory-board-outlines-recommendations-to-scale-up-carbon-dioxide-removals-while-addressing-opportunities-and-risks chapter 2. Unlike IEA op. cit., it sees an important role for nature-based solutions, but still expects BECCS potential at 150–250 Mt per year by 2050 see also p 330.

[4] Kevin Anderson and Glen Peters https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aah4567

[5] https://www.gasunie.nl/en/expertise/co2/carbon-capture

[6] https://www.iea.org/news/oil-and-gas-industry-faces-moment-of-truth-and-opportunity-to-adapt-as-clean-energy-transitions-advance

[7] https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/opec-head-accuses-iea-vilifying-fossil-fuel-industry-2023-11-27/

[8] https://climatenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/CAN-position_-a-fair-fast-full-and-funded-fossil-phase-out_-November-2023.pdf