Falling costs for solar, wind, and batteries are making renewables the dominant force in electricity. With speed and scale, they can deliver the emissions cuts we need – if politics doesn’t get in the way.

Remarkable predictions

The “Electricity 2025” report by the International Energy Agency contains a remarkable prediction: Global electricity generation by renewables will increase by more than 1,200 TWh this year. This is more than the anticipated total growth in electricity consumption.

In another report the IEA says renewable energy will overtake coal in 2025 and become the largest source of electricity. In 2026, both solar and wind electricity will each produce more electricity than nuclear power, and in 2029 solar power will deliver more electricity than hydro power.

Another projection for 2025 from the US Energy Information Administration says that new solar PV capacity will add 32 GW to the US grid. In this projection, the second-largest new power source is battery storage, with 18 GW, followed by 8 GW of wind power. All other sources together make up less than 5 GW of new anticipated capacity.

Low costs drive growth

Solar and wind electricity are growing fast because total generation costs have been falling (IRENA, 2024), and for the last few years have been lower than for any other way of producing electricity, almost everywhere in the world (Weforum, 2021; IEA, 2024).

The lowest public prices are between 1 and 2 US cents per kWh (EnergyWatch, 2024; WindpowerEngineering, 2017; PV magazine, 2020; PV magazine, 2021).

The rapid deployment of batteries is also the result of a rapid decrease in prices. Prices are falling because of the increased scale of production resulting from demand by the automotive industry and the industrial learning this entails. The latest reported price from China for battery storage, including 20 years of operation and maintenance, is given as 66 USD/kWh (Energy-storage news, 2024).

This price is, admittedly, exceptionally low. But all over the world batteries are being added to electricity grids, as they represent profitable investments even at higher prices.

Batteries serve many purposes

Today batteries are not only used to store renewable energy, but also to keep frequency and voltage stable, and provide what is called “synthetic inertia” (Hitachi energy, 2020). As a result they may take over the role of the large synchronous generators that are disappearing with the closing of large coal- and nuclear generators.

Renewable electricity also has many advantages.

Low total cost is not the only advantage of solar and wind power today. Because they do not use any fuels they do not produce air pollution or greenhouse gases as they generate electricity. The falling cost is partly a result of using less materials in manufacturing which means that the supply chains for turbines and solar panels now generate less pollution and require less energy than in earlier years (NREL, 2024).

The potential for accelerated deployment stems from another important feature of solar and wind deployment: The installation of solar or wind plants takes a few days, weeks or months, instead of many years or decades for coal or nuclear power plants.

In many countries, however, permission processes still require many years for wind power plants, as they do for any large power plant.

Behind the exponential growth

What takes more time is to build the factories that produce solar PV modules och wind power plants. In China, Jinko has started building a solar PV plant that is planned to have the capacity to supply modules with a generation capacity of 56 GW per year. Even so, it is only supposed to take two years to complete.

The world’s largest nuclear power reactors have a capacity of about 1.5 GW and take 5–20 years to build. When such a plant starts operating, it will deliver 1.5 GW of electricity.

The important difference is that the 56 GW solar module plant, when complete, will not deliver 56 GW of electricity, but every year will produce new solar power plants that can generate 56 GW (PV Magazine, 2024). This is one reason for the exponential character of solar growth in the world.

Renewable electricity can replace fossil fuels in industry and transport

While there are numerous publications and consultancy reports showing that the cost of solar and wind electricity is lower than fossil and nuclear electricity, there is another important achievement that is not so obvious: For the last few years renewable electricity has been cheaper than the price of crude oil (Kåberger, 2018). This is obscured by the fact that oil is traded with the price given as USD/barrel while electricity is traded in USD/MWh.

In the twentieth century electricity was produced from fossil fuels by thermal power plants with an efficiency of 30–50%. As a result, the price of electricity was roughly three times the energy price of the fuel used. With lower electricity prices, production would not be profitable and would come to a stop.

With solar and wind power taking over electricity generation, electricity could be cheaper than fossil fuels and therefore easily replace them.

Renewable electricity provides for cheaper, more efficient utilisation

Electricity is almost always easier to use than fossil fuels to provide the desired energy service. An electric motor is a simpler device than an internal combustion engine, and an electric boiler is simpler than a gas-fired boiler.

Even more importantly, heating efficiency can be drastically improved by using electric heat pumps.

As a result we can see how fossil fuels are being replaced in cars, buses, short-distance ferries and even airplanes with electricity stored in batteries.

But even some applications of fossil fuels that have until recently been considered hard to replace are becoming easy to replace as the cost of electricity cost falls. With electricity costs falling to the order of half the price of fossil fuels, it is possible to start using electricity to produce fuels (Kåberger, 2022). Initially this is likely to be for industrial purposes such as replacing coke in the reduction of iron ore (Hybrit development, 2024), or replacing fossil gas in the production of ammonia (Ammonia Energy Association, 2023).

New uses supplement batteries for balancing

Batteries are well suited to balancing variations in the production of electricity from solar or wind energy in timescales from fractions of seconds to hours and days. But wind variation requires flexibility over periods of weeks or longer. The industrial use of electricity to replace fuels may provide profitable balancing opportunities in these timescales. Either by storing hydrogen, as planned for hybrid steelmaking, or by simply flexing between electrolyser-based hydrogen production and conventional fuel-based production of hydrogen.

Profitable low-cost opportunities can accelerate development

Humanity will benefit if the energy industry continues to use the opportunities described above fast enough to avoid climate change at unmanageable speed, as well as nuclear weapon proliferation and war. As it becomes increasingly profitable to replace fossil fuels, expanding investment is desirable for the benefit of investors and the world at large.

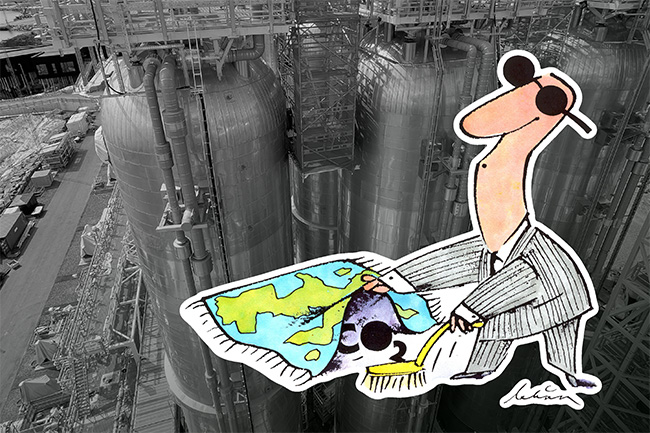

But there are also losers

For the fossil fuel industry, and those countries that depend on fossil fuel exports, there will be negative effects. They have good reasons to spend money to campaign against this industrial development. They know it cannot be stopped but also that it can be delayed.

Of the fossil-exporting countries, Russia is one of the largest and has done the least to develop renewable electricity. In addition to Russian campaigns (Greenpeace, 2022), private owners of fossil resources (the Guardian, 2025) and thermal power plants (Cleveland.com, 2023) are often active in delaying the growth of renewable electricity.

The IEA seems to believe the battle will be won by means of competitiveness in the market. While this is likely correct in the long run, the transition can be delayed by politics – as seen in some countries where Russian or fossil industry influence is strong.

With low-cost renewable electricity we can meet climate targets. The question is whether we will do so fast enough.