Wind power in the EU was 16 per cent up from 2012 and solar power was 17 per cent up. Photo: Argonne National Laboratory CC BY-NC-SA

Wind power in the EU was 16 per cent up from 2012 and solar power was 17 per cent up. Photo: Argonne National Laboratory CC BY-NC-SA

Denmark got 41 per cent of its power from the wind in the first six months of 2014. Renewables are advancing all over Europe.

Wind and solar are now big in absolute numbers, and of major importance to some countries.

Denmark got 41 per cent of its electricity from wind in the first six months of 2014, and another two per cent from solar. For shorter periods wind alone can supply more than 100 per cent of Denmark’s needs; the surplus is exported. Portugal got more than 25 per cent of its power from the wind, and Spain 21 per cent power from the wind (and 6 per cent from solar) in the first eight months of 2014.

Integration obviously works, in practice.

Portugal and Spain have some hydro that can balance the variability of wind and solar, but they do not have very much transmission capacity to third countries. Denmark has no hydro but can use export and import to balance demand.

Most countries can do either, well before issues of storage or demand-side management or new backup thermal power need to be addressed.

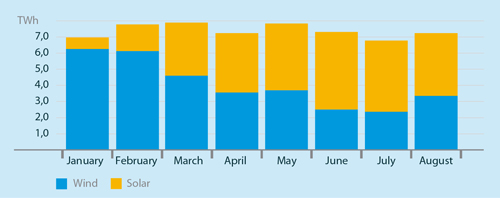

Germany, the world leader in photovoltaic solar energy, with 30 TWh in 2013, has also shown that it is easier to integrate both solar and wind power than either one of them. For the first seven months of 2014 a graph shows that the monthly total of wind and solar is almost constant (figure).

Wind power produced more than seven per cent of EU electricity in 2013, totalling 237 TWh, equivalent to the output of 34 large nuclear reactors or an even larger number of coal power plants. Wind power in the EU was 16 per cent up from 2012. Solar produced 83 TWh, 17 per cent up.

The share of wind and solar, and their growth, varies widely between countries for no very good reason. In 2013, Denmark got 33 per cent of its power from the wind, Sweden 7 per cent but Finland only 0.9 per cent. It is hardly likely that this can be explained by different wind strengths.

Spain, the top wind power nation in Europe, has almost four times as much wind power as France. Many ex-communist countries have very little wind power, for example Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary and the Baltic states (while Russia has none at all). Poland and Romania are now picking up, however.

The differences, whatever their cause, show that there is room for much more. Costs are being cut; the Danish government has found that (onshore) wind power is the cheapest option for new power. A recent US government study also shows that wind is cheaper than coal or nuclear. (Gas is still cheaper in the US, but not in Europe.)

Ten years ago the conventional wisdom was that renewables and efficiency were nice ideas, but the real way to cut CO2 emissions was coal with carbon capture, CCS, and nuclear power.

Now we know otherwise. CCS has got nowhere so far. Nuclear is declining in the EU. Its output fell 14 per cent between 2003 and 2013, from 999 to 878 TWh. Half of it is in France.

Meanwhile wind grew from 44 to 237 TWh, solar from 0.4 to 83 TWh and “other renewables”, excluding hydro, mainly biomass from 103 to 489 TWh.

As for efficiency, it is a fact that EU electricity consumption peaked in 2007 and has been dropping since then. Consumption of oil, gas and coal is also dropping. Energy demand is effectively de-linked from GDP.

All is not well. Some renewable subsidies have been poorly designed, with busts following booms. Retroactive legislation in Spain and Italy, for example, has scared off investors. Some governments are more interested in protecting the existing power companies than in the environment and climate.

But if the idea was to spread renewable tech from Europe to the world, it has worked.

China is now the world leader in wind and in photovoltaics, and many other countries are following suit.

Fredrik Lundberg

Figure: German production of solar and wind electricty in the first eight months of 2014.

Figure: German production of solar and wind electricty in the first eight months of 2014.